Brad DeLong has a blog post at the Equitable Growth blog called "Scene-Setting for the Policy Discussion: The American Economy Stumbles." The post is far too pessimistic about America's economic performance, especially over the period from 1980-2000. Here are a few points where I think Brad gets it wrong.

Brad's thesis is the following:

The American economy has done badly over the past generation or so.

This is not to say other economies have done better: The American economy remains among the richest in the world. However, given the economic lead America had a generation ago, it really ought to still be well ahead of the North Atlantic pack, and it no longer is.

I think this is a defensible thesis, if A) you define "a generation" as 15 years, and B) you deny that Solow convergence should take place at the higher levels of country income.

But in any case, I do not think that Brad successfully defends the thesis!

First, I think Brad dramatically understates the progress Americans experienced during the years from 1980 through 2000:

Across most of the income distribution Americans today are little if any better off than their predecessors back in 1979...Yes, today Americans have remarkable access to incredibly cheap electronic toys. But those are a small part of expenditure, and the costs of securing the standard indicia of middle-class life–a home in a safe neighborhood with good schools and a short commute, college for the children, assurance that a major illness will not lead to bankruptcy, a secure and reasonably-sized pension–have all become more costly relative to incomes. This shift is astonishing: For 150 years before 1979 Americans had confidently expected that each generation would live roughly twice as well in a material sense as its predecessor, not find itself struggling against the current to stay in the same place.

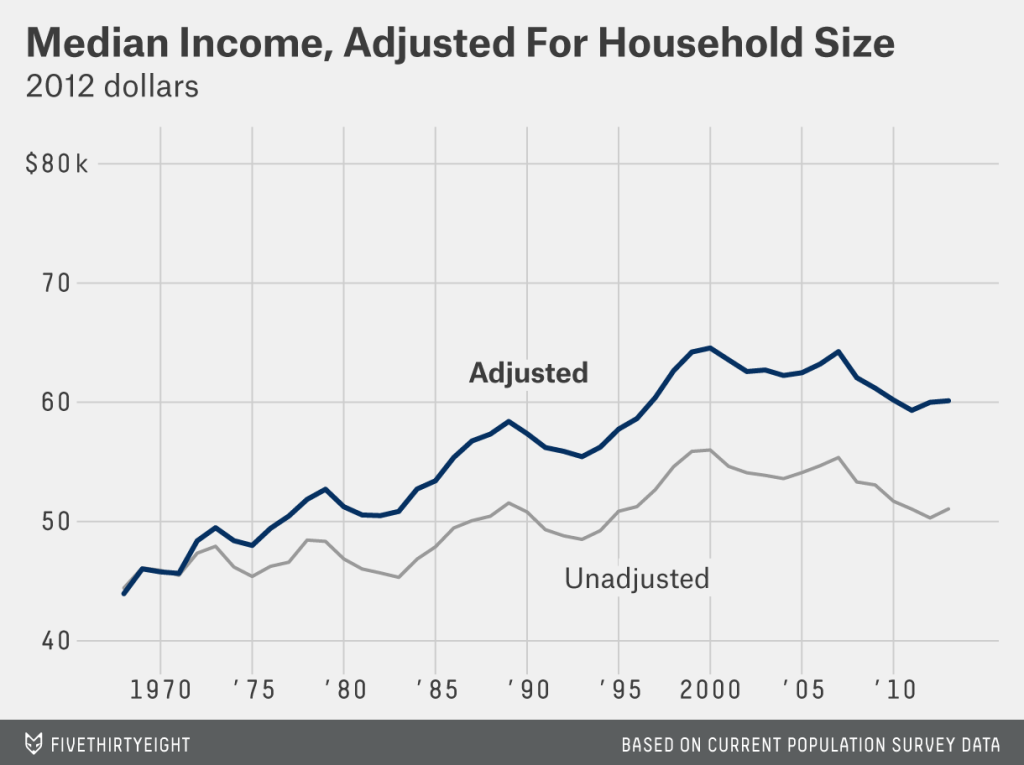

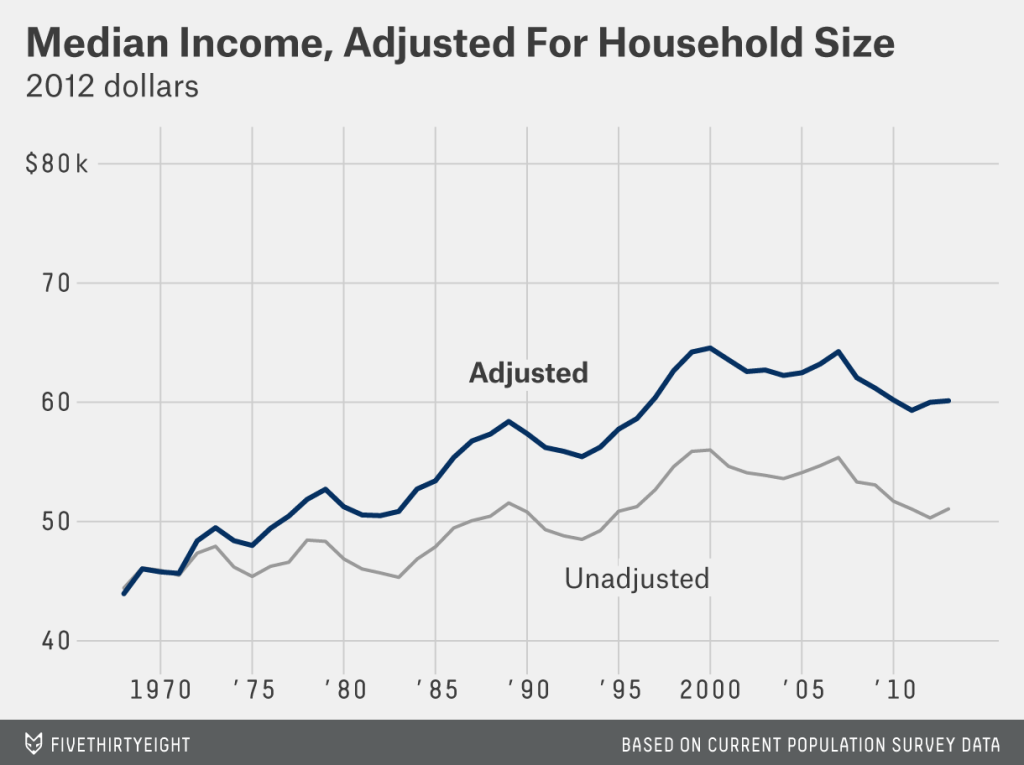

First of all, here is a picture of American median household income:

As you can see, even if we do not adjust for household size, the median American household experienced a substantial rise in income from the 1979 business cycle peak through the 2000 business cycle peak - around a 17% rise. But if you adjust for household size, the increase is around 23%, from a higher base.

Of course, this does not account for A) age, and B) composition. American households got much older from 1980 to 2000, and old people do not work much. Also, there was a boom in low-skilled immigration in the 1990s, which, although it boosted U.S. total GDP and was good for us overall, did tend to reduce the median income through composition effects.

Now, it is true that these figures also do not account for A) home production, and B) leisure. The entry of women into the workforce, which was not fully matched by male exit, meant that parents were spending less time with their children. And leisure did temporarily decline during the 1990s, after holding steady in the 1980s (then soared in the 2000s). So that mitigates the rise in living standards over the 1980-2000 period. But the truth is that in terms of purely material standard of living, the average American was substantially better off in 2000 than in 1980.

Anyway, Brad claims that the price of housing has gone up. He also claims that people (even well-off people!) live in smaller houses than in 1979:

The rest of the top 5% are about as rich as they might have expected. They have traded smaller houses and more burdensome commutes for more lavish vacations, cheap electronic toys, and greater social order.

House size, in fact, went up substantially between 1980 and 2000:

Also, I would argue that rent, not the price of a house, is the key measure of the cost of housing. Bubbles in the price-to-rent ratio merely offer households the opportunity for arbitrage. Here, via Mark Thoma and Robert Shiller, is a graph of real rents in the U.S.:

So even as house size soared, real rents stayed flat over the latter part of the 20th century. To me, that looks like a large increase in the standard of living of the average person.

What about the rest of Brad's "standard indicia of middle-class life," whose cost has supposedly soared? Regarding "a home in a safe neighborhood," the massive crime decline in the U.S. during the 1990s probably helped the lower and middle classes a lot more than the upper classes. Regarding "good schools," the performance of U.S. public schools remained flat or risen slightly relative to other countries, and in terms of NAEP scores, over 1980-2000 (and since). As for "burdensome commutes," this is true: average commute time increased by about 40 minutes per week from 1980 to 2000, and has been flat since 2000 - but this is an area in which new technology may be especially game-changing, since cell phones, texting, games, and podcasts/audiobooks make commuting much more fun. I get more "reading" done on my commute than during any other time.

It is certainly true that college has gotten much more expensive, health care bankruptcies have become more common, and pensions have become less generous (though this last is partly a function of Americans' increased consumption levels as a percentage of disposable income).

But then again, life expectancy has increased by about 5 years since 1980. That is not nothing. And many social indicators, including teen pregnancy and drug abuse, have decreased substantially.

Of course, all these numbers are just statistics - what about the lived experiences of Americans? Over the last two decades of the 20th century, Americans owned more cars, consumed more calories, had more TVs in their house, had bigger houses (as discussed above), and spent much less of their income on food, clothing, and shelter. These are things that mainly affect the marginal utility of the poor and middle class.

Brad's other main contention is that the U.S. is not doing well relative to other rich countries:

If you want a single set of numbers to keep in the front of your mind to understand America’s relative position today, you cannot do better than those in the figure below, copied from the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report:

The median American has only about $45,000 to his or her name, and wealth inequality as measured by the gap between the average and the median wealth is greater by far than in the typical rich country–only Sweden comes close. A generation ago it would have been ridiculous to even consider that the typical middle-class or working-class American might not lose if switched with the typical inhabitant of Australia or Italy or Japan or Finland or Singapore. It is not so ridiculous at all today.

Median net worth, of course, depends heavily on things like asset prices; the number for the U.S. dropped by more than half as a result of the housing bust. Other countries, like Canada, did not experience a housing bust. Also, net worth depends heavily on age, and the U.S. is younger than many of the countries listed above us in the median wealth ranking.

But more fundamentally, is median wealth the proper measure of living standards? Wealth is a function of savings rates, and savings rates depend on consumption levels, which are a choice. During the 1980s and 1990s, Americans chose to consume more of their income than our peers in most rich countries (though this has recently reversed itself in some cases, e.g. in Japan). If you look at median disposable income, the U.S. was ahead of every other rich country except Canada in 2010, despite some convergence:

As you can see, the U.S. was still ahead of the North Atlantic pack in 2010. Only Canada caught up (and we'll see how well that holds now that oil prices have crashed). We still comfortably beat Sweden, Germany, Britain, the Netherlands, and France. Japan is not listed, but the pattern is the same.

If this income disparity continues to hold, then the U.S. can climb back up the median wealth rankings whenever it feels like it - just save more out of disposable income. (Note: This graph does NOT prove that U.S. median standards of living are higher than these other countries, since those numbers are before transfers, and also do not take into account things like transport, crime, pollution, health, nice weather, or good fashion sense. But it DOES show that Americans could climb up the wealth rankings over time, if they wanted to.)

So in conclusion: Bad Brad! In 2000, you believed that American economic policy and the American economy, though far from perfect, had been largely a success (right?). It's understandable to think the 15 years since then have been a big disappointment - they have! - but why should that cause you to revise your evaluation of the period from 1980 to 2000? Do you think that we are now paying for excesses we enjoyed in that period, and that our prosperity increases during that period were thus illusory? I don't think you think that. So don't succumb to excessive pessimism!

No comments:

Post a Comment